I have no rigorous philosophical schooling so I admit I'm using many terms somewhat instinctively. I thank you for the above remark because it helps make the point even clearer. I see that Scott has practically addressed this in his post.Eugene I wrote: ↑Sat Nov 20, 2021 10:16 pmCleric, I understand what you are saying. Indeed, the ability of consciousness to cognate and experience meanings is amazing an mysterious and allows for the rich and interconnected universe of meanings to exist in consciousness. However, in philosophical terms phenomenology does not study the meanings and their inter-relations with themselves and with the rest of reality, that belongs to epistemology. Phenomenology studies the raw conscious phenomena themselves, as was quoted from philosophical encyclopedia at the start of this thread, including all sense perceptions, feelings, thoughts and imaginations, and their qualia, but not including the meanings and ideas that the thoughts and imaginations bear. The challenge with studying the meanings is related to their complicated relations with the rest of reality (consciousness itself and the raw phenomena).Cleric K wrote: ↑Sat Nov 20, 2021 8:48 pm Let's make this fully clear.

Phenomenology doesn't imply that every conscious perspective is guaranteed to have access to every phenomena by default. This is not true even in the sensory spectrum. For those who have been in Egypt the Pyramids are sensory phenomena. I've never been there so I assume that they exist. Can I be absolutely certain? Not really. What if I'm in the Truman Show and this whole world is a set up that decided to make me believe there are pyramids while there aren't any. All movies, books, photos - everything is a part of a great conspiracy against me. And this is not as absurd as it sounds. Flat Earth conspiracy, Moon conspiracies and what not, show that the human psyche is fully capable of getting in such modes.

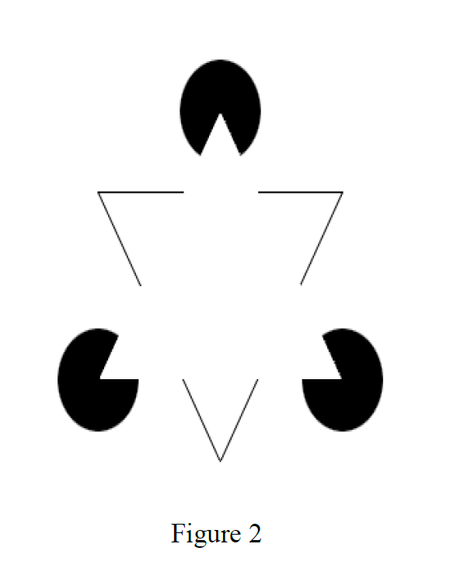

I don't know what else I can say without repeating what Scott and Ashvin already pointed out. The GR image practically illustrates the point of overlap between phenomenology and epistemology, between the raw phenomenon and the meaning. This is at the core of PoF where they are called perception and idea. The GR metaphor speaks about completely the same things, it just tries to utilize the intuition that we have developed by delving into scientific thinking.

My example with the verbal thought from the previous post aimed precisely to show that tiny piece of curvature of meaning which completely explains the raw phenomena of verbal thoughts which follow its geodesics. This is the point of overlap. Here meaning is not simply post factum interpretation of the thoughts (raw phenomena) - they are interlocked into a sacred dance.

I'm sure you're familiar with Wheeler's words "Space-time tells matter how to move; matter tells space-time how to curve". Although this places everything in the abstract third-person view, we can still intuit something from it. With our spiritual activity we're weaving in meaning. Meaning is not a raw phenomenon that we observe in the field of consciousness. Instead it is the invisible geometry of consciousness, the meaning curvature of which makes sense of the way raw phenomena move.

You keep thrusting down both raw phenomena and meaning as mere contents of consciousness. Actually you can never thrust down meaning in this way. What is being thrust down is the thoughts that symbolize this meaning. In other words you seek to experience consciousness as something beyond both phenomena and meaning. And this is the simple reason why your meditations remain inexplicable. How could they ever be explicable if meaning is thrust down as mere details, while one imagines that true reality is to be found in the inexplicable 'experiencing'. This is at the core of the mystic soul mood. One strikes out meaning as something that has only provisional value for intellectual life in the body, while reality is sought in something that forever remains a buzzing vortex of confusion from the standpoint of the intellect. This is the duality that everyone here tries to point out. It is based on the prejudice that meaning (and thus ideas) serve only to give some handles for the intellect to operate in the sensory spectrum but in itself can not lead to reality. The most important thing to notice here is that ultimately this is a conclusion of the thinking intellect. It is the intellect which philosophizes that thoughts and meaning are only floating fragments and they must be thrust down in order to delve into the inexplicable, which the intellect believes to represent a deeper level of reality.

In the overlap of thinking we have first-person spiritual activity which curves meaning and thus determines the movement of raw phenomena. There simply is no other example in our consciousness, where we can experience meaningful activity which engineers in such an intimate way the phenomena. Now if we have this living example where meaning shapes reality, what gives us the confidence that this can be simply stricken out as irrelevant and we should succumb in the inexplicable instead? How many more years of meditation on the inexplicable we have to go through before our thinking concludes that the only way the inexplicable can become explicable is if it becomes meaningful. This is the contradiction of mysticism and also the reason of its concealed dualism. The so called consciousness seeks to experience itself as the ground reality, yet doesn't want to experience any meaning to it because the latter is considered inferior, second order manifestation of consciousness. This puts everything in a paradoxical situation because any meaning smells to the mystic of "I"-being but at the same time the "I"-being can only live in meaning and thus is cut clean from the supposed 'reality' of consciousness. So the mystic's "I"-being dissipates meaning into a cloud of inexplicable confusion, where it half-consciously believes that in this way it lives closer to the heart of reality.

We must really understand that we create this hard problem for ourselves. It is thinking which declares its impotence to penetrate reality. It says "The meaning in which I live is only a second order manifestation of the ground being". But how does thinking reaches this conclusion? How can this be known as a certain fact and not only as a belief? It cannot be known. Because the intellect, by its own self-definition dissolves when it tries to approach the first order reality.

Let's look at two great polar approaches to reality.

One of them is Schop-like mysticism where meaning is assumed to exist as spread out dark inexplicability in the World Will but gradually becomes swirled into focused lucid loci in human beings. So even though the such condensed world will, now experiencing itself as intellect, is assumed to be of the same essence as the ground being and thus Schop considers that the Kantian divide is resolved, the fact remains that the intellect can only abstractly conceive of all of this. If it was to verify this, it would have to begin tracing the steps of condensation in the reverse direction but this would only lead to less and less meaning, as the focus of meaning becomes more and more blurry and everything sinks into the inexplicable once again. So ultimately the reality of the blind Will can never be known. It forever remains within the intellect as a mental picture of that which is supposed to exist beyond the event horizon at which meaning dissolves into the inexplicable. So we see that the Kantian divide is not truly resolved because even though the intellect assumes the blind will to be the first order reality, this reality can never be known as such. It can be conceived only as a mental picture in the intellect, which even though of the same essence, is still a second order organization. This is effectively the same soul mood we have in materialism, pan-psychism and what not. The first order reality is assumed to possess the potential for thinking living in meaning but the latter is considered only a second order folding, twisting, curving of the ground being. When this curvature is complex enough it becomes possible that the primordial potential rises its head above the dark abyss and is awestruck by the peculiar situation in which it finds itself. I think every modern person can wholeheartedly understand this position not only intellectually but as living experience.

The other pole is the theistic, where it is assumed that the ground being of reality is infinitely aware, containing all potential to create out of itself everything. Here the Kantian divide is once again not in the least resolved because it is considered blasphemous by most to believe that the human soul and God's Consciousness experience reality from the same side (Mobius strip). Instead the soul is seen as opaque bubbles created by the Divine.

Now PoF shows precisely the way to attain to the proper integration of these two tendencies. This essential core is commonly missed for two main reasons. The first is purely technical - one has the good will to understand but simply fails to, similarly to the way one fails to understand some mathematical problem. The second is that one consciously or subconsciously feels that proper understanding will ruin the comfort of current conceptions (because the nature of PoF is such that once understood, something objectively changes in our organization and we can't simply undo that). After all this time it's still unclear to me what is Eugene's case and that's why I continue to participate in these discussions.

Consider this drawing by Escher:

The mystic's philosophy sees only one aspect of the picture. He sees meaning as coagulating packets of inexplicability which when sufficiently organized become meaning. The theist on the other hand sees everything as emanating from the pole of absolute meaning. All this remains quite abstract unless we understand how it plays out in thinking. Thinking is the intersection of these two streams.

If we conceive of the meaning within thinking only as a second order coagulation of primordial inexplicability, it's natural that the higher we build the tower of Babel (thoughts upon thoughts), the more it seems we're moving away from the true ground of reality and into the clouds. And this is really the case with all the abstract science and philosophy of today. Strings, MAL, alters - all of this builds the tower. This is not to say that everything is completely useless, as in the Sisyphus myth. It's still exploration of degrees of freedom but it will never be anything more than abstract tower of thoughts unless we understand how the other pole of the Cosmic Polarity plays out.

The pole of meaning is just as real as the pole of the ground raw phenomena. When we turn the picture of Escher around, then we can see all meaning not as coagulation of inexplicability but as diminished meaning, as aliased meaning, primordial perfect meaning out of which holes have been cut out. When the holes are small it feels as if we're living in a completely meaningful Cosmos, where the holes move along the curvature of living ideas (invisible meaning). But when the holes become much greater than the light, it feels as if the Cosmos is mainly a mystery, a conscious phenomenon and only here and there we have sparks of meaning that give the intellect some sense of what's going on.

So we have two Cosmic Poles - one is the Pole of Mystery, the Cosmic raw phenomenon which in itself is inexplicable. The other is the Pole of Meaning, the grand Idea (in Goethe's sense) which is the perfect meaning of all and we have mystery phenomena only where the Idea has been hollowed out. In the GR metaphor the Pole of Mystery is the perceptual phenomena of mass/energy, the Pole of Meaning is the Cosmic curvature of meaning which makes sense of the phenomena's movement.

I believe most readers will understand this on the abstract level. The question is how to approach it as something real and not simply as floating sparks of intellectual thoughts. The only place we can start the process is thinking itself because this is the only place where we find real interplay of the two poles. It is the only place where we find curvature of meaning in conjunction with raw phenomena flowing along its geodesics. So it is from the point of concentrated thought that the holes of Mystery can begin to be filled with the Light of meaning.

This process is asymmetric. Just as Time. In fact, they are secretly related. The equations of physics look like Escher's painting. Scientists look at them, scratch their heads and ask "Why time flows along with the one flock of birds and not the other?" Then begin to spin wild theories about entropy and the likes. When we understand the picture through the Great Poles, the answer comes by itself. Time can flow only in the direction of increasing meaning, which on our everyday level is most readily grasped as increase of memory (every moment of life adds some meaning/knowledge, even if it is simply the awareness that we have moved forward in time and now we encompass more of our life). The whole problem comes because of the Kantian divide through which we keep insisting that the world (and thus time) exists in itself and as such time and its direction are attributes of that world. Our consciousness is simply dragged along and we try to understand why the world-in-itself drags in this direction and not the other. When we understand reality from the first person perspective, the answer is self-evident. Time can be experienced only as buildup of meaning. In the intellect we conceive of this as living and aging in a physical Cosmos with no clue why, in the spirit it is the continual filling of the holes of mystery with meaning. This filling is not monotonic but in rhythmic iterations. Sleep is the clearest example. We can never experience how we fall to sleep precisely because it's not possible to experience stream of consciousness where every next state is less conscious than the previous. But the rhythmic integration continues in the morning (or to some extent while dreaming).

So the key to PoF is to understand that even though the meaning of the intellect looks only like tiny sparks, it is of the same essence as the Absolute Meaning. One difficulty with this is that the modern mind is so addicted to reductionism that it simply can't conceive of meaning as the holistic essence of reality. It can see meaning only as accumulation of atoms into a mechanical complex. For this reason people see God as some kind of super intellect, as inconceivably complex computer. But the Absolute Idea is actually the simplest thing. It is the perfect sense, perfect unity, perfect wholeness, perfect clarity, perfect completeness. All existence flows in Time as integration of meaning between the two poles. At the poles at infinity themselves there's no existence in Time. The light of perfect meaning is the same as the darkness of complete mystery. Outside of Time they are one and the same. Yet between the two, consciousness can be experienced as a stream in Time only in the direction of the Light of meaning.