The Game Loop

Part 6

Concentration

Part 6

Concentration

Google Doc version (easier to follow footnotes)

Part 1 Mental Pipelines

Part 2 Interleaved IO Flows I

Part 3 Interleaved IO Flows II

Part 4 In Search of the Fundamental Inputs I

Part 5 In Search of the Fundamental Inputs II

Part 6 Concentration

In our attempt to gain a more intimate experience of the way we interface with the game loop, we were gradually led to our inner life of thinking and imagination. Even though we are far from having unconditional control over these IO flows, they nevertheless present us with a much more in-phase experience of the way intuitive inputs and mental outputs correlate. Compared to that, our feeling and willing offer a more complicated resistance, as if there are more hidden factors that interfere with our inputs. It is as if there’s greater leeway; there are more ways our inputs can end up being out of phase with the outputs. Yet, at the same time, when we reach our mental IO flow, it seems we hit a limit. Even though we try to grasp what kinds of ‘buttons’ and ‘sticks’ we operate in order to produce a thought, we simply end up producing more mental images in the same nebulous way. We find ourselves at the event horizon where we instinctively, yet with some intuitive directedness, push toward a future state. When we say that we push toward the future, this doesn’t imply some movement through a temporal dimension of reality but only the bare facts of experience – namely, that our ever-present state continuously transforms. In the phenomenological outputs of this ever-present flow, we continuously become aware of the consequences of our intuitive pushing. We recognize how the compounding mental images (which are immediately already of the nature of memory images) have something to do with our dim inputs.

The reader may still have their doubts about whether what we speak of corresponds to reality. Such doubts can only arise as long as one is reluctant to feel themselves actively willful in their inner inputs. And in our particular age, this is somewhat understandable. We have already seen in the first part how both scientifically minded people and those mystically inclined have a kind of aversion, even fear, of this experience. At the intellectual surface, these feelings are rationalized as a kind of prudence based on sound understanding. One says, “I just don’t want to fall into an illusion, I don’t want to be like all those superstitious people who believe that there’s something real in their sense of agency.” Yet, whether we like it or not, this sense of agency is a given fact of our inner experience. Even when one denies it, like in the above sentence, one still utilizes it. Paradoxically, it is as if one secretly declares: “All forms of intuitively willed inputs are illusions except when I use these inputs for declaring them to be illusions.” Of course, one will hardly admit this because it immediately reveals an inner inconsistency. If one needs to be consistent, they would have to declare the denying thought to be just as illusory and doubtful as the affirming one1. We are not here to tell whether the sense of agency is real or not, but only to elucidate that it is possible to utilize that agency in such a way that more and more phenomenal outputs are grasped as receding impressions of intuitively guided will.

The above-mentioned limit is only there as long as we insist on finding the IO interface as a part of the output. With the risk of being repetitive, we need to direct attention to this tendency once again, since it is extraordinarily stubborn. Even if we conscientiously aim to overcome it, it easily happens that, even without noticing, we snap back to it like a broken record. It is rooted in a deeply ingrained sense that, in our intellectual sphere, we can inflate indefinitely to encompass all aspects of reality as mental images. We secretly seek some hypothetical God-like perspective that can place itself above all reality and contemplate its imagined potato pipeline as spread out at our feet. This keeps us seeking a symbolic replica of the true event horizon as a nicely shaped output-to-output process experienced through stacking mental images. The trouble is not that we make a symbolic mental image of the horizon. Even in our phenomenological approach we are doing that, but we only use it as a pointer to the actual experience. The problem is when we silently declare that the picture-in-picture potato modeling is the one and only way of knowing the essence of reality.

We need to realize that this inability to locate the true horizon in the output field is not some arbitrary handicap of human cognition that we should compensate for through more mental modeling, but an intrinsic aspect of reality. If we ignore that aspect, we are striking out a fundamental given in the mystery of existence. We act like trying to solve a maths problem where we arbitrarily dismiss some of the given conditions, and then wonder why we can’t find a non-ambiguous solution. We simply need to investigate things as they are, instead of trying to fit them into our preconceived expectations. We need to get comfortable with the fact that we can never behold the horizon of becoming in the way our intellect desires – as a mental or perceptual object that can be contained within our phenomenal volume. Instead, the horizon can only be intuitively known through the experience of continuous becoming – the precipitation of phenomenal states that reflect something of our intuitive pushing.

So, is it possible to deepen this experience and make it practically useful, instead of simply noting it as some peculiar end-limit of our cognitive abilities? To answer this, let’s remember how, when we think about our mental process, we switch from one kind of thinking to another. For example, when we are fully engaged in solving the chess puzzle from the previous part, we are busy stacking mental images according to our intuition of what next moves are compatible with the present state. However, to arrive at the reflection in the former sentence, we need to stop solving the puzzle and switch to a different kind of mental flow, one in which we are stacking memory images of our past psychological states of solving the puzzle. These two mental flows are largely incompatible; they are conversations on two different coffeehouse tables – we can switch from flowing through one or another, but cannot grasp them together simultaneously. What about when we think about the psychological reflection itself? Now we once again switch to a new kind of mental flow, which, however, is more similar to the one being examined in memory. They both stack memory images of psychological states, except that they are recursively related. We can even enter a flow where we reflect on the reflecting about the reflecting about the puzzle flow, and so on. This, however, besides being a peculiar mental exercise, doesn’t lead too far either. Our ordinary thinking and imagination can be compared to a walk through a gallery where we’re completely absorbed in the paintings we see (constituting the picture-in-picture flow), while our intuition about the walking itself, the fact that we are in a gallery, and so on, remains in the background. On the other hand, when we think about our psychological states, it is as if we walk through a gallery where the paintings aim to depict that very fact.

This is still a step forward, because now our mental picture-in-picture flow (the succession of paintings) aims to represent something of the wider context of the primary flow. They become more self-similar; they are like video feedback where we experience the stacking reverberations of our momentary first-person phenomenal states. Nevertheless, as long as we strive to find the reality of our total real-time flow of becoming within the picture-in-picture mental flow, we still feel like the dog chasing its tail or like the hands trying to capture their real-time activity in the picture – the output of our mental images is always one step behind our real-time intuitive input.

But what if we change our strategy? Can we assume an inner stance that is more akin to the clay artist? Instead of trying to deaden our real-time flow by seeking its reality only through contemplation of its already past output snapshots, can we innerly position ourselves within that real-time flow and simply experience the precipitating mental images as dynamic, close to real-time, feedback to our intuitive artistic pushing? We can indeed do that, and we can begin with very simple experiments.

We can take a pencil and try to very slowly draw a curve while we are completely focused on the tip of the pencil. There shouldn’t be any jerks of attention, no skipping, no inner chatter. For at least a second, we should try to move the tip in a completely smooth, slow, and continuous manner, tightly following it with our gaze. It is very easy to see how we can become distracted. Our hand may continue to draw on ‘autopilot’ while our mental flow is carried over in some completely different direction, or our eyes continuously snap to other perceptions in our visual field. To make this exercise even more focused, we can take it entirely in our imagination. In this way, we reduce as far as possible the inherent leeway between intuitive inputs and bodily output perceptions. Now we can move the pencil tip, or simply the focal point of our attention, in our mind’s eye, while still trying to do so slowly and smoothly, avoiding any interruptions, any skipping of attention. As we try to do that, we aim to contemplate as closely as possible how the mental output2 is almost in perfect phase with the inputs of our intuitive intents. The key here is that we should no longer separate the two sides of our experience. We should not leave the movement on autopilot while we go on to philosophize about it in our inner voice. Neither should we surrender to completely passive contemplation and expect that the point of attention should move by itself, in the way outputs in our sensory-visual field do.

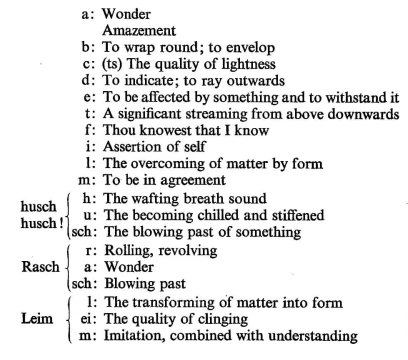

A similar exercise can be performed by producing a continuous vowel sound with our inner voice and slowly and smoothly morphing it through different vowels (a, e, i, o, u). This exercise is especially valuable because it helps us close the leeway even further. When we move the focal point of our attention, we still have the implicit feeling that we are ‘here’ and we focus on a point within phenomenal space ‘over there’. When we focus on the sound of our inner voice, the experience is even more intimate. We may actually discover that while we were focusing on the movement of attention, our inner voice was still mumbling something in the background. When we consciously engage in the shaping of inner sound, such background mumbling becomes practically impossible because we find ourselves unable to split our inner voice into two – one which produces a continuous vowel sound and another which comments in words.

Such experiments with our inner voice can be of the greatest value. We may find a strange tendency that fiercely resists such an exercise. There could be a strange, uneasy feeling when we experience our inner voice so consciously, much like we may feel when we hear our physical voice on a recording. We would much rather let the exercise free-fall instinctively, while we only oversee and comment from the background. If we are not clearly aware of this tendency, even if we try such exercises, it may happen that we secretly perform them as if we observe someone else doing them, or we vaguely imagine what it could be if we were to do them. This gives us a feeling of security that our inner sense of self, secretly hidden in the background, is safe and immutable. It is implicitly assumed that any such exercises only concern the reconfiguration of some output phenomena at a distance, while the goal is precisely to experience more closely the process that produces the reconfiguration and comments from the background. This reluctance to approach the process of shaping our inner mental gestures needs to be overcome if we are to gain a deeper experience at the IO interface. The two are simply mutually exclusive. We cannot attain deeper intuition for the way inputs are impressed in the outputs if we are unwilling to actively explore the only place where this can be found as an actual experience. If we refuse to approach this experience, we may try to build some theoretical picture about it, we may picture someone else going through it, but that mental picture will always feel remote and unrelated to the true inner inputs hidden in the background, which speak the theoretical thoughts or imagine what the experience of the exercise could be like. As long as our cognitive process remains instinctively proceeding from the background, we have the false security that we can pre-calculate everything in our mind before entering into contact with the wider flow. However, here it is precisely the goal to become lucidly aware at the threshold where even our pre-calculating thoughts (i.e., the background mumbling) can no longer be pre-calculated (we can’t think before we think). We need to get the clear feeling that we’re at the threshold between the known (past) and the unknown (future), and be willing to observe how even our inner voice precipitates as something that we could not have perceived as imaginative output before we have intuitively pushed into the unknown next state.

Granted that the reader has the goodwill to follow along this path of inner experience (otherwise, what follows simply won’t make much sense), we nevertheless stumble upon the next obstacle. It is enough to attempt these focused exercises even for a second to realize that it often feels like trying to draw a smooth line with our hand amid a battlefield. We are constantly assailed from all directions by influences that very easily throw us off track. We can illustrate this process in the following way:

Here, we start with our focused mental activity (the vertical line starting from below), but then, at the moment of distraction, we are thrown into another IO track. The nature of this moment is very elusive since, in general, we do not have clear awareness that we are being distracted. This is deeply related to the way we fall asleep each night. Normally, we do not have consciousness of “I’m awake, and now I transition into sleep.” Instead, it is as if we lose consciousness, and when we eventually become aware within a flow of dream imagery, our dream state lacks the well-compounded intuitive context that makes us implicitly aware of our progression through waking life3. Things change when we transition to a state that reunites the two flows. In the morning, we find ourselves in a state that coheres the intuitive compounding of both the dream stream and that of the previous waking life up to the moment of falling asleep. Something completely analogous, yet on a much smaller scale, happens in our moment-to-moment mental flow. As soon as we become distracted, it is as if we fall asleep; we lapse into a daydream flow where the intuition of “I’m concentrating my mental activity” is no longer present. Instead, we continue daydreaming through the new stream, and only when the two IO flows ‘cross paths’ again, we experience their superimposed intuition, and we say, “Oh, I was trying to concentrate on the exercise, but at some point I got distracted and switched flows.”

What does it mean that we got distracted? It means that some unknown factor beyond the power of our focused input has nudged our flow into a differently shaped riverbed. Here, the physicist or biologist would immediately object, “But such unknown factors are only mirages in consciousness. In reality, there’s nothing ‘nudging’ our ‘flow’. It is all an emergent picture of fundamental physical processes.” The fact, however, is that even if we call these nudges mirages, this in no way makes it possible to ‘walk through them’. From a phenomenological perspective, when we speak of such nudging forces, we are not in the least postulating any metaphysical processes that ‘explain’ them. As long as we’re focused on the bare facts, we can’t go wrong. It is to these bare facts that we point when we speak of nudging forces, not to some speculative glowing energies. In other words, we are concerned not with mental stacks that try to explain what causes these forces, what stands behind them, and so on, but only with the most immediate fact that our intuitive input is being modified and thus the actual output differs from the intuitively anticipated one.

Through some effort and persistence, it is possible to resist such nudges. Just like we need some strength training if we are to stay on our feet when nudged by a crowd, so we need a certain strength of mental input if we are to maintain the intended curvature of our inner flow. What is interesting is how the inner nudges are now experienced. They certainly feel like some unknown factors that compel us to think about this or that, but when we try to resist them, these nudges are experienced from within our first-person flow, similar to an imaginative flash accompanied by intuitive insight. In a sense, we become conscious of in what direction our inner flow might have gone if the switching had not been arrested in time. Interestingly, even though the flow didn’t switch completely in that direction, from within this flash of insight, we intuitively know quite a lot about how it would have turned out were we to follow it. It is like these nudges push us off-course only enough to be conscious of the intuitive curvature specific to their flow, but not so far that we fall asleep, and only later awaken and reunite the streams.

We should try to get a feeling for the effort needed here. It is one of intense vigilance. The mental image that we have chosen for anchoring our attention (we can even use the focal point of attention itself) is of secondary importance. It can be compared to a ridge that the clay artist shapes by holding their finger steady while the pot turns on the wheel. Even though the shape of the ridge seems static, it is the result of continuous steady activity. If someone pushes the artist’s hand, a bump in the ridge would be formed. The same idea can be conveyed through the image of the seismograph.

Here, the needle tip symbolizes our focused sustaining of the mental image. A concentrated activity would result in a straight line, while all perturbations in the gravity field result in wiggles. The ridge and the graph line must be understood in the sense of the stacking chess-puzzle frames, and not as a spatial line, nor as some temporal dimension. Both metaphors suggest that the resulting impressions only testify to the effects of the forces. In other words, we do not see the reality of the nudging forces in the mental outputs. This is very important to understand, because otherwise we can easily fall into a certain naivety if we believe that the imaginative flashes constitute the objective reality of the nudging forces. This would be like believing that the perturbing forces affecting the seismograph are contained and act from within the line ink.

Seen in this way, the output mental image at our focus is only the near-real-time feedback of how well we are stabilizing our intuitive input activity, how free of interruptions it is, and how well we resist the perturbations to our ‘steady mental needle’. When we strive to intercept the potential nudges and thus avoid the interruptions, it feels as if we try to ‘split the moment’. We concentrate ever so finely, such that we do not ‘miss a beat’. If we blink, we may miss the moment, and we are off into the dream ridge, only later to reunite again with our intentions.

Splitting the moment

It should go without saying that when using an expression like ‘splitting the moment’, we should by no means imagine some fantastic output blob that we call a ‘moment’ and then try to split it in the way we split a cotton ball into smaller balls. No, the ‘splitting’ is an artistic expression for the way we try to shorten the leeway between our intuitive inputs and the outputs in our imagination, for example, when we move the imagined pencil tip. We strive to decrease as far as possible any slack between intent (input) and image (output) because it is in between the two that we fall asleep and switch tracks. Another metaphor that we can use to illustrate this idea is that of stroboscopy. Here, we have short flashes of light that illuminate the environment, followed by periods of darkness.

It is as if in these dark periods of sleep, the switching of flows occurs. Thus, ‘splitting the moment’ is like focusing our attention so tightly as if we want to increase the strobing rate, such that we do not miss anything. This metaphor also provides another valuable intuition. We can see that if the strobing happens at the appropriate times, the perceived dynamics may be different from the actual. This is exemplified by the wagon wheel effect.

Here, the strobing is produced by the camera’s shutter, but the effect would be the same if we were looking at the disc in a dark room and there was a strobe light flashing at the same rate as the camera’s frame rate. This metaphor will become more relevant later in the series. At this time, it is enough to consider how there’s a lot that we may be missing in our inner flow, and that the intuitive story that we compound by stacking the illuminated frames may not fully coincide with what we would experience if more frames were alit.

Such activity of intensified attention (increased strobing rate) and experiencing the nudges as we resist them, seems complicated and speculative only as long as we are busy philosophizing about it. As soon as we put the philosophizing aside and actually try it, everything becomes clear on its own. We quickly understand what all these words are pictures of. Even if we utterly fail to resist the nudges, the attempt in itself already gives us a rich first-person intuition about this process. Least of all, we would no longer be able to deny that we’re dealing with real experiential factors of our existential flow. What is real is not our fantasies about what might stand ‘behind’ these forces, nor is the imaginative content of the flash their ‘objective’ reality, but the experience of the nudging compulsion in itself – the fact that we’re forced to flow through this or that riverbed of experience. All our concepts and images are only attempts to symbolically convey these real experiences.

We’ll continue to explore this direction in the next part of the series. Here we only need to become familiar with the idea that by striving to sustain a certain ‘shape’ of our inner flow, we begin to gain consciousness of factors that normally shape our stream of becoming with very little awareness on our side. As a simple example, let’s say that while we try to concentrate, something continuously tries to push us into a riverbed where we daydream through scenes of our favorite TV show. By resisting this push, we achieve two things simultaneously. First, we became conscious that such a tendency indeed exists. We may have never before been fully awake to the fact that we spend quite a lot of time free-falling through such daydreams. Second, by resisting the nudge, we become conscious that we are, in fact, able to do so. In a way, we become aware of what ‘muscles’ we are activating in order to counteract the nudge. As an analogy, if we stand in a crowd pushing us from different directions, by trying to stay straight, we may become aware of how we instinctively activate different muscles depending on whether the push is coming from the front, the side, etc. Similarly, we try to concentrate and stabilize our flow more or less instinctively, yet as we resist the distracting forces, we also become conscious of unsuspected ‘input muscles’, which, when mastered, allow us to navigate the landscape of interfering nudging forces in new ways.

Keynotes:

-----

1 This, however, immediately leads to a paradox again (known as the liar’s paradox). If our thinking is inherently illusory and unreliable (thus both denying and affirming thoughts are doubtful) then even the statement about its unreliability can no longer be trusted! This keeps the intellect cycling through the contradictory statements.

2 This mental output doesn’t need to be anything vivid – it’s more than enough that we have some sensation of where our ray of attention is pointed. Anyone can sense whether their focus is more to the left side of their forehead or the right. It is this pointing of attention that we need to sharpen, turning into a laser beam, so to speak, and tightly experience its movement.

3 Reflecting deeper on such facts can help us appreciate how the compounded intuitive sense for the story of our life is found at the ‘tip’ of our flow of becoming – that is, our ever-present state. For example, we may say, “But I positively remember that I was doing so and so yesterday. I was ‘there’.” Yet, we can do a thought experiment and imagine that the game state has been somehow ‘manually’ assembled into our present state and the game loop was ‘started’. Effectively, it is impossible to tell whether we have really lived through the past states or it only seems so from within the intuitive context of our present state. Such lines of thought have been explored in science fiction, such as the movie Total Recall (based on a novel). If we could be implanted with sensory and emotional memories of having been on an exotic vacation (and not remembering the implantation), would we feel the same satisfaction that we were ‘there’ as if we really had been? In our dream states we have something comparable, where we become aware within a partial intuitive context. Often we dream of being in different places, at different times, without really questioning them, since we have no awareness of going to sleep. We do not remember that we have other life in the waking state. Each of these dream states feels like the tip of the flow of becoming, that compounds the intuition of its unique story. An interesting case is that of lucid dreaming, where we reunite with some of our waking intuition while still in the dream state.