"...test all things; hold fast what is good." - 1 Thessalonians 5:21

We briefly discussed, in Transfiguring our Thinking (Part I), that our spiritual (thinking) activity is the only activity where the phenomenal appearances and the noumenal 'thing-in-itself' are unified. This equivalence is known because it is our activity which produces the phenomena. For all other perceptions we can ask, "what is the meaning of this object? why do I perceive this object? what stands behind this perception?" For our thought-forms, these questions are answered by the very nature of thinking. I know what they mean because it is my idea projected into the thought-forms. I know why I perceive them because I will the thought-forms into existence. I know that it is my own ideating activity which stands behind the thought-forms!

This final installment of the Metamorphoses of the Spirit essay will explore the spiritual implications which unfold from that one simple fact about our thinking activity (used interchangeably with "spiritual activity"). It is important to keep in mind that we are not seeking an "absolute" Reality which is external to the human perspective and the human way of knowing. Such an endeavor is simply a fool's errand. The human perspective may expand or contract, perhaps it will even encompass what we now call a 'non-human' perspective at another time, but we can never assume it is possible to know anything external to this perspective, whether we are engaged in philosophy, science, or both.

Although I may write like I am very familiar with this topic we are exploring together, I myself cannot be counted among those who have experienced the full implications of what we will discuss. Not even close. I am still merely investigating these deepest issues with my abstract intellect; organizing and expanding my thoughts for my own benefit, most of all. If others find it helpful as well, then that is icing on the cake. We must be clear that the mere intellectual understanding is not sufficient. Eventually we must arrive at corresponding experience and feeling which accompanies such an understanding, brought forth from within.

Nevertheless, what we learn here in abstract concepts prepares our soil for the seeds to be planted within us later, so that our plants may grow and flower in full health. In that sense, it is an invaluable exercise. It is like venturing into unknown territory with a map prepared for us - the map is a small, two-dimensional rendering with little icons and shapes which look nothing like the three-dimensional territory being mapped. Yet, who among us would prefer to leave the map behind when entering? If we carry the map with us, then we will find it a lot easier to navigate the territory and understand what exactly we are encountering along the way. Let us first consider an example of what was asserted above:

Imagine you are looking at an object shaped with a circular form, without any clear thought about the form (percept). The percept observed without thought arrives to your senses in a 'mysterious' way. Now imagine you look away from the object and retain the picture in memory without thought. Still the picture remains a mystery. While perceiving the inner image of the percept, you say to yourself, "a circle is a figure in which all points are equidistant from the center". Only now have you added the proper concept to the percept and can understand what you are seeing.

There are many different forms of circles one can perceive - small, large, red, blue, etc. - but there is only one concept of "circle" shared by all. For most percepts, their mysteriousness remains until they are linked with other percepts and the proper concepts. They point us towards something external to us for their explanation. With pure thought-forms, however, the percept arrives with its proper concept at the same time. One can think of a "circle" and the thought of the circle is the circle itself. It does not point us towards anything external for its explanation. If you are still confused, don't worry, because we will explore this unique essence of thinking much more.

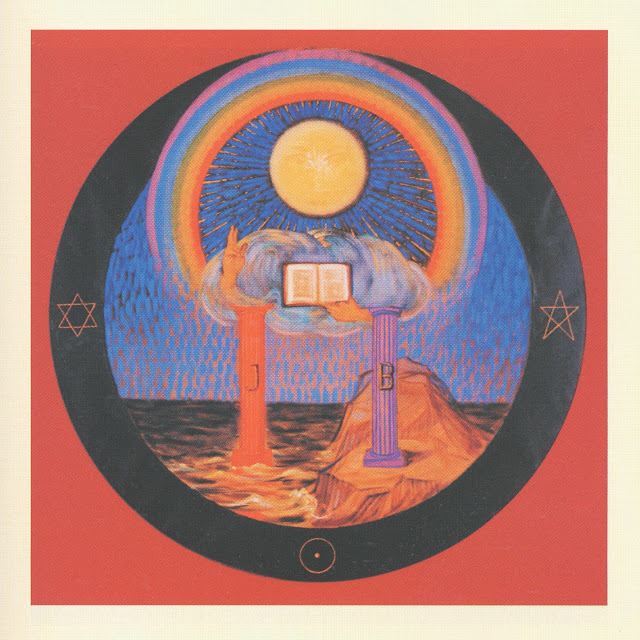

Our next step is to recognize that our thinking activity is the most recent development in the metamorphic process, as we discussed in Breaking Bad Habits. If we want to take a good look at the core of human spirituality, we must first undress its garment which was put on most recently. Our spirit guide in this endeavor will be Rudolf Steiner, who was the most profound and prolific exponent of the Spirit's metamorphoses. In The Philosophy of Freedom (or Spiritual Activity), written at the end of the 19th century, he provides answers to the deepest riddles of man in the most simple and straightforward manner. It is a truly revelatory experience to read his writings.

I am not asking anyone to take Steiner's assertions below on faith. The metamorphic process has no more use for blind faith. Instead, we must "test everything" and "hold fast what is good", as Saint Paul told the Thessalonians. We should read and re-read as many times as we require to see how it all holds together. Our tool at this stage will be the one used so well by medieval thinkers like Saint Thomas Aquinas - thoughtful contemplation. We will try and recapture the art of thinking from that age, when individuals could sit in monastic isolation for many hours with nothing but their thoughts of the Divine. All that was written before in this series was preparing our pack in base camp for the long hike up this mountain, and now our quest for true knowledge begins.We are now in a period when a significant change must come about: People must become thinking people instead of thinking machines. It is terrible, is it not, when you say something like that, because people of our time take it for granted that they are thinking people, and if you ask them to become thinking people, they actually find it an insult. But that is how it is.

Since the middle of the 15th century, people have become more and more like thinking machines. People surrender themselves to thoughts, as it were; they do not control them. Imagine what it would be like if you did the same with your limbs as most people do with their thinking organs today. Ask yourself if the modern human being can be inclined – I say can be – to randomly take in a thought and randomly shut down a thought. Thoughts are bubbling up in people’s heads today. People cannot resist them; they automatically surrender to them. A thought arises, the previous one disappears, it flies and flashes through the mind, and people think in such a way that one could best say: it thinks in the human being.

Imagine that your arms and legs would behave similarly, that you would be able to control them as little as you can control your thinking. Imagine a person walking down the street, his arms moving in the same uncontrolled way as his thinking organ moves! You know how much goes through a person’s head when he walks down the street, and now imagine how he would continually gesture with his arms and hands in the same way that he does with the thoughts in his head!

And yet, we are facing the age when people have to learn to control their thoughts in the same way they control their arms and legs. We are entering that era. A particular inner discipline of our thinking is what has to occur now and from which people today are still exceedingly far away."

- Rudolf Steiner, The Mental Background of the Social Question (1919)

For the reason Steiner outlined above, we must begin observing and thinking about our own process of thinking in its dynamic living transformations, carefully taking note of what that process reveals in us. We will start this phenomenological approach by taking note of how exactly the world of appearances presents itself to us. Thinkers like Immanuel Kant assumed the 'external' world of appearances came to us in a complete form. Individual humans, then, must somehow create within themselves a self-contained model of ideas which approximates that 'external' world in order to gain true knowledge. How can such a Herculean task be accomplished?I have spoken until now about thinking without taking any account of its bearer, human consciousness. Most philosophers of the present day will object that, before there can be a thinking, there must be a consciousness. Therefore consciousness and not thinking should be the starting point. There would be no thinking without consciousness. I must reply to this that if I want to clarify what the relationship is between thinking and consciousness, I must think about it. I thereby presuppose thinking. Now one can certainly respond to this that if the philosopher wants to understand consciousness, he then makes use of thinking; to this extent he does presuppose it; in the usual course of life, however, thinking arises within consciousness and thereby presupposed it. If this answer were given to the world creator, who wanted to create thinking, it would without a doubt be justified. One cannot of course let thinking arise without having brought about consciousness beforehand. For the philosopher, however, it is not a matter of creating the world, but of understanding it. He must therefore seek the starting point not for creating, but rather for understanding the world. I find it altogether strange when someone reproaches the philosopher for concerning himself before all else with the correctness of his principles, rather than working immediately with the objects he wants to understand. The world creator had to know above all how he could find a bearer for thinking; the philosopher, however, must seek a sure basis from which he can understand what is already there. What good does it do us to start with consciousness and to subject it to our thinking contemplation, if we know nothing beforehand about the possibility of gaining insight into things through thinking contemplation?

We must first of all look at thinking in a completely neutral way, without any relationship to a thinking subject or conceived object. For in subject and object we already have concepts that are formed through thinking. It is undeniable that, before other things can be understood, thinking must be understood. Whoever does deny this, overlooks the fact that he, as human being, is not a first member of creation but its last member. One cannot, therefore, in order to explain the world through concepts, start with what are in time the first elements of existence, but rather with what is most immediately and intimately given us. We cannot transfer ourselves with one bound to the beginning of the world in order to begin our investigations there; we must rather start form the present moment and see if we can ascend from the later to the earlier. As long as geology spoke of imagined revolutions in order to explain the present state of the earth, it was groping in the dark. Only when it took as its starting point the investigation of processes which are presently still at work on the earth and drew conclusions about the past from these, did it gain firm ground. As long as philosophy assumes all kinds of principles, such as atoms, motion, matter, will, or the unconscious, it will hover in the air. Only when the philosopher regards the absolute last as his first, can he reach his goal. This absolute last, however, to which world evolution has come is thinking.

- Rudolf Steiner, The Philosophy of Freedom (1894)

Kant's epistemic "solution", or, more accurately, his abandonment of the pursuit, came in his claim that each individual takes categorical judgments and unconsciously spreads them over the real world before perceiving the results (discussed with more detail in Res Ipsa Loquitur - Kant vs. the World). Therefore, we are always and only perceiving the phenomenon we ourselves have imposed on the world rather than any aspect of the 'thing-in-itself'. We do not take notice of our ongoing acts of creation and, even if we did, we cannot ever undo them. Although most philosophers in the wake of Kant did not even attempt to challenge this epistemically nihilistic claim, a few brave ones tried to circumvent it.

Most of them made little headway or simply continued speculating from a third-person perspective which pretends to stand apart from the world, a method which Kant had already ruled out (appropriately). One in particular, though, does stand out from the rest and deserves mention - Arthur Schopenhauer. He recognized there is a fundamental aspect of all beings which we can experience in the absence of any other phenomenon - our will. If we were to be placed in a sensory deprivation chamber without sight, sound, taste, touch, or smell, then we would still experience our will. Why Schopenhauer fell short can be observed from what he is leaving out from the category of "phenomenon" - precisely our thought-forms.

Schopenhauer can say, at best, that our willing plus our thinking is always experienced. Anything short of that is abstractly speculated from our thinking activity rather than being rooted in the givens of our experience. Schopenhauer cannot possibly claim universal Will exists without ideal content. To fully internalize the point I am making, we should remember that we can only philosophize from what we experience via our first-person perspective as human beings (as Kant understood), because we cannot know anything external to that perspective. Some would call that approach "solipsism" and I am not opposed to that characterization, except I would call it "healthy solipsism".

I am not claiming our limited ego is the only thing we can know exists, which is what I call "unhealthy solipsism". Rather, we are admitting in humility that all we logically derive from outside our first-person experience is an assumption which, whether actually true or untrue, we cannot verify empirically in any case. So, what can any person, including those who enter deep mystical states, claim to have experienced? It will become obvious that, no matter what we experience in the 'deprivation chamber', when any ideal content is expressed, either to ourselves internally or to others, we are already in the presence of thinking activity.

Schopenhauer cannot justifiably claim that there is Will in the absence of ideal content. He is adding an unverifiable assumption that experiences can exist without ideal content. There is no good reason why this assumption would be warranted. Schopenhauer assumes that which cannot, under any circumstance, be directly perceived in the given - the assumption that his will is identical to the will of others i.e. the universal Will, and the latter is only mixed with ideas in some limited representational domain. Yet that assumption is itself a product of thinking activity - the quintessential example of sawing off the branch on which one is sitting.

These conclusions will be resisted fiercely because the Kantian stranglehold is so tight that even the brightest philosophers will ignore the ever-present role of thinking when reasoning through these questions. As Owen Barfield remarked, "the obvious is the most difficult thing of all to point out to anyone who has genuinely lost sight of it". Today, thanks to the metamorphic forces which influenced Descartes and Kant (among others), we have lost sight of the 'interior' Cosmos where thinking takes place. Schopenhauer's insight, however, is not altogether useless to our endeavor. The blind spot in Schopenhauer's argument regarding thinking activity also points us toward the proper correction to Kantian epistemology.

If Kant had realized from the beginning that the world of percepts does not arrive as completely formed to our sense organs, then his entire endeavor would have been rendered moot. He would have noticed that the nature of our organization after birth (more specifically, after "object permanence" develops) has split the noumenal world into two phenomenal parts, the subject and the object. That split happens at the level of each individual person as we discussed in the first part of the essay when considering Piaget's developmental psychology. Therefore, the objects we perceive are only partially complete and it is our thinking activity which reunifies what we originally tore asunder.

Valentin Weigel was a 16th century German mystic who realized the true import of what Kant only realized later in a superficial manner. Our sensory organs are indeed adding ideal content to the bare percepts, but only if our thinking capacity is considered a sensory organ for the reasons we have discussed throughout this series. It does not add ideal content according to arbitrary or superficial rules. Rather, it matches the percepts with their appropriate concepts and, moreover, all beings who share in the Spirit which makes us human appear to perform this operation in a similar (but not exactly the same) manner. Our thought-forms, perceived by thinking, belong to the phenomenal world just as much as sights, sounds, tastes, and smells.Since in natural perception there must be two things, namely the object or counterpart, which is to be perceived and seen by the eye, and the eye, or the perceiver, which sees and perceives the object, therefore, consider the question, Does the perception come from the object into the eye, or does the judgment, and the perception, flow from the eye into the object.

- Valentin Weigel

All "objects" are, in essence, continual progressions of forms and it is our thinking which allows us to recognize them as such. With that ever-so-slight modification of our perspective, Kant's entire epistemic edifice crumbles beneath the weight of its Truth. We then begin to see the outlines of man's spiritual activity - an activity which puts back together all that we originally split apart in our Fall. Yet we are not merely putting the world back together - there is also something gained by the world in the process which could not have existed in its ever-present Origin. We will return to that later, but let us first examine my assertion above more closely and, hopefully, to our satisfaction with the help of Steiner (all remaining quotes sourced from The Philosophy of Freedom).It is quite arbitrary to regard the sum of what we experience of a thing through bare perception as a totality, as the whole thing, while that which reveals itself through thoughtful contemplation is regarded as a mere accretion which has nothing to do with the thing itself. If I am given a rosebud today, the picture that offers itself to my perception is complete only for the moment. If I put the bud into water, I shall tomorrow get a very different picture of my object. If I watch the rosebud without interruption, I shall see today's state change continuously into tomorrow's through an infinite number of intermediate stages.

The picture which presents itself to me at any one moment is only a chance cross-section of an object which is in a continual process of development.

- Rudolf Steiner, The Philosophy of Freedom (1894)

We should take a moment to appreciate what Steiner is doing here - unlike any philosopher which came before him, or after him for that matter, Steiner is starting from zero of the standard philosophical assumptions about the nature of Being-Nothing, Ideal-Real, Spirit-Matter, Absolute-Contingent, Will-Thought, Good-Evil, etc. He is simply asking us to consider what we observe in our own experience and how our thinking unfolds in relation to what we observe. No philosophical background is necessary, nor any background in theology or science, bur only a desire to follow Steiner's clear imagery and the simple line of reasoning he employs.Steiner wrote:When I observe how a billiard ball that is struck communicates its motion to another, I remain thereby completely without influence on the course of this observed occurrence. The direction of motion and the velocity of the second ball are determined by the direction and velocity of the first. As long as I act merely as observer, I can say something about the motion of the second ball only when the motion has occurred. The matter is different when I begin to reflect on the content of my observation. My reflection has the purpose of forming concepts about the occurrence. I bring the concept of an elastic ball into connection with certain other concepts of mechanics, and take into consideration the particular circumstances which prevail in the present case. I seek, that is, to add to the occurrence that runs its course without my participation a second occurrence that takes place in the conceptual sphere. The latter is dependent upon me. This shows itself through the fact that I can content myself with the observation and forgo any seeking for concepts, if I have no need of them. But if this need is present, then I will rest content only when I have brought the concepts ball, elasticity, motion, impact, velocity, etc. into a certain interconnection, to which the observed occurrence stands in a definite relationship. As certain as it is, now, that the occurrence takes place independently of me, it is just as certain that the conceptual process cannot occur without my participation.

...

That this activity appears to us at first as our own is without question. We know full well that along with objects, their concepts are not given us at the same time... The question is now: What do we gain through the fact that we find a conceptual counterpart to an occurrence?

Why does it matter if we can be assured that our thinking, unlike any other activity or content of our experience, is brought forth from ourselves? Here we must remember the purpose of delving into the Spirit's metamorphic progression in the first place - it was to find an anchor from which we could rediscover our participation in the world-evolving process. Here we mean "participation" in the sense of Lucien Levy-Bruhl ("participation mystique") and Owen Barfield ("original participation") - the actual co-creation of the phenomenal world. We must rediscover that participation if we are to begin viewing the world contents as multi-dimensional images with interiority rather than flat 'things' with only exterior surfaces.Steiner wrote:Whatever principle we may ever set up: we must show that it was somewhere observed by us, or express it in the form of a clear thought which can also be thought by everyone else. Every philosopher who begins to speak about his ultimate principles must make use of the conceptual form, and thereby of thinking. By doing so he admits indirectly that he already presupposes thinking as part of his activity. Whether thinking or something else is the main element of world evolution, about this nothing yet is determined here. But that the philosopher, without thinking, can gain no knowledge of world evolution, this is clear from the start...

Now with respect to observation, it lies in the nature of our organization that we need it. Our thinking about a horse and the object “horse” are two things which for us appear separately. And this object is accessible to us only through observation. As little as we are able, by mere staring at a horse, to make a concept of it for ourselves, just as little are we capable, by mere thinking, to bring forth a corresponding object.

...

But as object of observation, thinking differs essentially from all other things. The observation of a table or of a tree occurs for me as soon as these objects arise on the horizon of my experiences. My thinking about these objects, however, I do not observe at the same time. I observe the table, I carry out my thinking about the table, but I do not observe my thinking at the same moment. I must first transfer myself to a standpoint outside of my own activity, if I want, besides the table, to observe also my thinking about the table. Whereas the observing of objects and occurrences, and the thinking about them, are the entirely commonplace state of affairs with which my going life is filled, the observation of thinking is a kind of exceptional state. This fact must be properly considered when it is a matter of determining the relationship of thinking to all other contents of observation.

...

To regard thinking and feeling as alike in their relationship to observation is therefore out of the question. The same could also easily be demonstrated for the other activities of the human spirit... It belongs precisely to the characteristic nature of thinking that it is an activity which is directed solely upon the observed object and not upon the thinking personality. This manifests itself already in the way that we bring our thoughts about a thing to expression, in contrast to our feelings or acts of will. When I see an object and know it to be a table, I will not usually say that I am thinking about a table, but rather that this is a table. But I will certainly say that I am pleased with the table. In the first case it does not occur to me at all to express the fact that I enter into relationship with the table; in the second case, however, it is precisely a question of this relationship.

...

The reason why we do not observe thinking in our everyday spiritual life is none other than that it depends upon our own activity. What I do not myself bring forth comes as something objective into my field of observation. I see myself before it as before something that has occurred without me; it comes to me; I have to receive it as the prerequisite for my thinking process. While I am reflecting on the object, I am occupied with it; my gaze is turned to it. This occupation is in fact thinking contemplation. My attention is directed not upon my activity, but rather upon the object of this activity. In other words: while I am thinking, I do not look at my thinking, which I myself bring forth, but rather at the object of my thinking, which I do not bring forth.

It should be clear from Steiner's writing that nothing for him is a merely abstract question of human knowledge. Rather, because the world is, in reality, "indivisibly united", all ontology and epistemology for him is meaningful only to the extent that it has real practical implications for our thought and behavior in the world. We are not only thinking beings who live in a realm of ideal relations which unify us with the world, but also individual personalities willing and feeling in relation to those living ideas. The key for Steiner is that willing and feeling as individuating activity must not be substituted for thinking as a unifying activity.Steiner wrote:I am, as a matter of fact, in the same position when I let the exceptional state arise and reflect on my thinking itself. I can never observe my present thinking; but rather I can only afterward make the experiences, which I have had about my thinking process, into the object of thinking... The thinking that is to be observed is never the one active at the moment, but rather another one...

Two things are incompatible with each other: active bringing forth and contemplative standing apart. This is recognized already in the first book of Moses. In the first six-world days God lets the world come forth, and only when it is there is the possibility present of looking upon it. “And God saw everything that He had made and behold, it was very good.” So it is also with our thinking. It must first be there if we want to observe it.

...

In every case the dualist finds himself compelled to set impassable barriers to our faculty of knowledge. The follower of a monistic world conception knows that everything he needs for the explanation of any given phenomenon in the world must lie within this world itself. What prevents him from reaching it can be only accidental limitations in space and time, or defects of his organization, that is, not of human organization in general, but only of his own particular one.

It follows from the concept of the act of knowing as we have defined it, that one cannot speak of limits to knowledge. Knowing is not a concern of the world in general, but an affair which man must settle for himself. Things demand no explanation. They exist and act on one another according to laws which can be discovered through thinking. They exist in indivisible unity with these laws. Our Egohood confronts them, grasping at first only that part of them we have called percepts. Within our Egohood, however, lies the power to discover the other part of the reality as well. Only when the Egohood has taken the two elements of reality which are indivisibly united in the world and has combined them also for itself, is our thirst for knowledge satisfied — the I has then arrived at the reality once more.

Willing, feeling and thinking all form a Tri-Unity of experience. In the metamorphic history of Spirit, there was a time when Cosmic thoughts were experienced by humans as 'external' sensations (Jean Gebser's "archaic-magical" consciousness). After the Incarnation of Christ, there was a reversal of experience in which those same Cosmic thoughts were experienced from within. Willing and feeling, then, are soul processes which renew the Cosmic thoughts within and carry them forward into the future of humanity. That is a very crude summary of a monumental topic, but I include it simply so we are clear that willing and feeling play indispensable roles in the metamorphic progression of Spirit.

Let us consider those bolded words a bit more. We will briefly turn to another great exponent of the human soul - Carl Jung. Anyone familiar with Jung will recognize the importance of the word "shadow" in his psychology. Jung's concept of the shadow is precisely the "counter-image" Steiner speaks of above. It is all of that ideal content which we refuse to bring into the light of our thinking consciousness. In many cases, the primary reason it is repressed is due to the responsibility which naturally follows from each individual's spiritual capacity. That capacity reminds us that we all too often self-impose limits on our thinking because it is much easier to deal with a spiritual realm remaining forever beyond our cognitive reach.Steiner wrote:The difficulty of grasping the essential nature of thinking by observation lies in this, that it has all too easily eluded the introspecting soul by the time the soul tries to bring it into the focus of attention. Nothing then remains to be inspected but the lifeless abstraction, the corpse of the living thinking. If we look only at this abstraction, we may easily find ourselves compelled to enter into the mysticism of feeling or perhaps the metaphysics of will, which by contrast appear so “full of life”. We should then find it strange that anyone should expect to grasp the essence of reality in “mere thoughts”. But if we once succeed in really finding life in thinking, we shall know that swimming in mere feelings, or being intuitively aware of the will element, cannot even be compared with the inner wealth and the self-sustaining yet ever moving experience of this life of thinking, let alone be ranked above it. It is owing precisely to this wealth, to this inward abundance of experience, that the counter-image of thinking which presents itself to our ordinary attitude of soul should appear lifeless and abstract. No other activity of the human soul is so easily misunderstood as thinking. Will and feeling still fill the soul with warmth even when we live through the original event again in retrospect. Thinking all too readily leaves us cold in recollection; it is as if the life of the soul had dried out. Yet this is really nothing but the strongly marked shadow of its real nature — warm, luminous, and penetrating deeply into the phenomena of the world. This penetration is brought about by a power flowing through the activity of thinking itself — the power of love in its spiritual form.

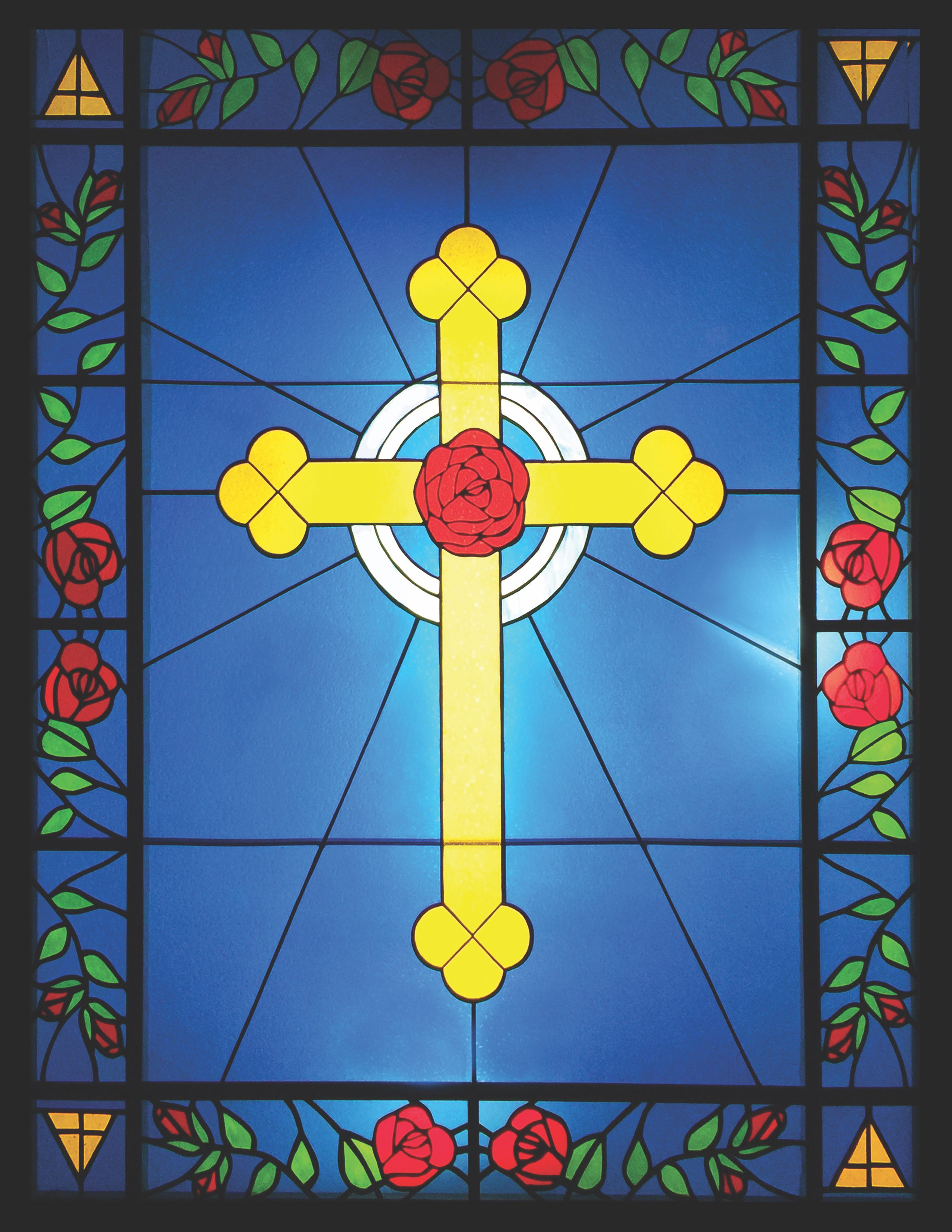

It is frightening how often we take the word "Spirit" as a placeholder for "supernatural thing" in the fragmented modern world; to talk about it in a serious tone but without any concrete substance within the world we experience. Steiner shows us, more than anything else, how the living and breathing activity of our Spirit is immanent to our everyday experience if we simply slow down a bit to pay it some well-deserved attention. In such contemplation, we are developing our capacity for spiritual freedom, that is, Self-determination. And from that capacity for spiritual freedom all humans possess, our entire moral imagination unfolds as a beautiful rose from its stem.

Steiner then brings us to a genuine ethics which necessarily follows from the Reality of our spiritual nature. The most common objection to this "ethical individualism" is that human beings must be given boundaries for their actions or else they will do whatever they please and such free actions will harm others in the process. This objection assumes humanity is currently in a complete state of being, which is a thoroughly anti-metamorphic assumption. Without such prejudice, we can admit that the human being who must be compelled by legal fiat or social norm to refrain from harming others is many things, but one thing he most certainly is not - free.Steiner wrote:The first level of individual life is that of perceiving, more particularly perceiving through the senses. This is the region of our individual life in which perceiving translates itself directly into willing, without the intervention of either a feeling or a concept. The driving force here involved is simply called instinct. The satisfaction of our lower, purely animal needs (hunger, sexual intercourse, etc.) comes about in this way. The main characteristic of instinctive life is the immediacy with which the single percept releases the act of will. This kind of determination of the will, which belongs originally only to the life of the lower senses, may however become extended also to the percepts of the higher senses. We may react to the percept of a certain event in the external world without reflecting on what we do, without any special feeling connecting itself with the percept, as in fact happens in our conventional social behaviour...

The second level of human life is feeling. Definite feelings accompany the percepts of the external world. These feelings may become the driving force of an action. When I see a starving man, my pity for him may become the driving force of my action. Such feelings, for example, are shame, pride, sense of honour, humility, remorse, pity, revenge, gratitude, piety, loyalty, love, and duty.

The third level of life amounts to thinking and forming mental pictures. A mental picture or a concept may become the motive of an action through mere reflection. Mental pictures become motives because, in the course of life, we regularly connect certain aims of our will with percepts which recur again and again in more or less modified form. Hence with people not wholly devoid of experience it happens that the occurrence of certain percepts is always accompanied by the appearance in consciousness of mental pictures of actions that they themselves have carried out in a similar case or have seen others carry out... The driving force in the will, in this case, we can call practical experience...

The highest level of individual life is that of conceptual thinking without regard to any definite perceptual content. We determine the content of a concept through pure intuition from out of the ideal sphere. Such a concept contains, at first, no reference to any definite percepts. If we enter upon an act of will under the influence of a concept which refers to a percept, that is, under the influence of a mental picture, then it is this percept which determines our action indirectly by way of the conceptual thinking. But if we act under the influence of intuitions, the driving force of our action is pure thinking...

Kant's principle of morality — Act so that the basis of your action may be valid for all men — is the exact opposite of ours. His principle means death to all individual impulses of action. For me, the standard can never be the way all men would act, but rather what, for me, is to be done in each individual case.

...

When Kant says of duty: “Duty! Thou exalted and mighty name, thou that dost comprise nothing lovable, nothing ingratiating, but demandest submission,” thou that “settest up a law... before which all inclinations are silent, even though they secretly work against it,” then out of the consciousness of the free spirit, man replies: “Freedom! Thou kindly and human name, thou that dost comprise all that is morally most lovable, all that my manhood most prizes, and that makest me the servant of nobody, thou that settest up no mere law, but awaitest what my moral love itself will recognize as law because in the face of every merely imposed law it feels itself unfree.”

This is the contrast between a morality based on mere law and a morality based on inner freedom.

We should also mention Nietzsche in this context, who wrote: "And I dwell within my house, and have imitated no one, and laugh at every master who has never laughed at himself". Barfield expresses a similar sentiment as he remarks: "Man alone can deliberately will the repetition of an experience... yet it is the enemy of life, for repetition is itself the principle, not of life but of mechanism." The free spirit finds itself metamorphosed from the purely reactive instinctual life and monotonous intellectual life into the imaginative and inspirational life of ethics. It recognizes itself as a work in progress that has only scratched the surface of its true creative and moral potential.

With the Incarnating the Christ installment, we considered Barfield's philological phenomenology of the Spirit, in which he concluded the patterned change in language meanings observed throughout the world around the centuries leading into the 1st century A.D. can only be explained by that which is recorded in the Gospels, even if one had never heard of such Gospels before. In other words, one would have needed to invent the narrative of Christ found in the Gospels to "save the appearances" of such transformations in language. Now we have seen why the same could be said of Steiner's phenomenology of spiritual activity and its path to freedom.Steiner wrote:Just as monism refuses even to think of principles of knowledge other than those that apply to men, so it emphatically rejects even the thought of moral maxims other than those that apply to men. Human morality, like human knowledge, is conditioned by human nature. And just as beings of a different order will understand knowledge to mean something very different from what it means to us, so will other beings have a different morality from ours. Morality is for the monist a specifically human quality, and spiritual freedom the human way of being moral.

...

Ethical individualism, then, is not in opposition to a rightly understood theory of evolution, but follows directly from it. Haeckel's genealogical tree, from protozoa up to man as an organic being, ought to be capable of being continued without an interruption of natural law and without a break in the uniformity of evolution, up to the individual as a being that is moral in a definite sense. But on no account could the nature of a descendant species be deduced from the nature of an ancestral one. However true it is that the moral ideas of the individual have perceptibly developed out of those of his ancestors, it is equally true that the individual is morally barren unless he has moral ideas of his own.

...

Ethical individualism, then, is the crowning feature of the edifice that Darwin and Haeckel have striven to build for natural science. It is spiritualized theory of evolution carried over into moral life.

Anyone who, in a narrow-minded way, restricts the concept of the natural from the outset to an arbitrarily limited sphere may easily conclude that there is no room in it for free individual action. The consistent evolutionist cannot fall a prey to such narrow-mindedness. He cannot let the natural course of evolution terminate with the ape, and allow man to have a “supernatural” origin; in his very search for the natural progenitors of man, he is bound to seek spirit in nature; again, he cannot stop short at the organic functions of man, and take only these as natural, but must go on to regard the free moral life as the spiritual continuation of organic life.

...

The mature man gives himself his own value. He does not aim at pleasure, which comes to him as a gift of grace on the part of Nature or of the Creator; nor does he fulfill an abstract duty which he recognizes as such after he has renounced the striving for pleasure. He acts as he wants to act, that is, in accordance with the standard of his ethical intuitions; and he finds in the achievement of what he wants the true enjoyment of life. He determines the value of life by measuring achievements against aims. An ethics which replaces “would” with mere “should”, inclination with mere duty, will consequently determine the value of man by measuring his fulfillment of duty against the demands that it makes. It measures man with a yardstick external to his own being.

The view which I have here developed refers man back to himself. It recognizes as the true value of life only what each individual regards as such, according to the standard of his own will. It no more acknowledges a value of life that is not recognized by the individual than it does a purpose of life that has not originated in him. It sees in the individual who knows himself through and through, his own master and his own assessor.

The heart of the Christian faith rests in the pursuit of spiritual truth and freedom, regardless of dogma or creed. It is a faith which asserts that, when we seek and know the truth, then and only then will it set us free. That truth we seek is none other than the Spirit which only satisfies us when we "first lend it that magical power by which it uplifts and gladdens us". It is the truth of our noble human character; our integrality in bringing the Cosmos back into harmonious relationship. We not only put back together what we split apart, but add to the world a realm of moral imagination. When the Spirit takes up His dwelling within us, our faces will shine like the Sun and our garments will become as white as light. Only that is worthy of free beings.

What we discussed above is the difference between being originally born and being born again in the Spirit; not metaphorically, but literally. What on Earth made this rebirth possible? To whom should we give thanks for this remarkable opportunity? Here I do not part company with the Church's ecclesiastical tradition. It is truly Christ incarnate in Jesus of Nazareth who made it possible and we need only give thanks to Him and our Father in Heaven. For those who find that distasteful or impossible to accept, I can only recommend they carefully [re]consider the previous parts of this essay. For everyone else, the quest for true spiritual knowledge has only just begun.

Steiner wrote:Whoever seeks another unity behind this one only proves that he does not recognize the identity of what is discovered by thinking and what is demanded by the urge for knowledge. The single human individual is not actually cut off from the universe. He is a part of it, and between this part and the totality of the cosmos there exists a real connection which is broken only for our perception. At first we take this part of the universe as something existing on its own, because we do not see the belts and ropes by which the fundamental forces of the cosmos keep the wheel of our life revolving.

...

Thinking destroys the illusion due to perceiving and integrates our individual existence into the life of the cosmos. The unity of the conceptual world, which contains all objective percepts, also embraces the content of our subjective personality. Thinking gives us reality in its true form as a self-contained unity.

...

To recognize true reality, as against the illusion due to perceiving, has at all times been the goal of human thinking. Scientific thought has made great efforts to recognize reality in percepts by discovering the systematic connections between them. Where, however, it was believed that the connections ascertained by human thinking had only subjective validity, the true basis of unity was sought in some entity lying beyond our world of experience (an inferred God, will, absolute spirit, etc.).

...

Man finds no such primal ground of existence whose counsels he might investigate in order to learn from it the aims to which he has to direct his actions. He is thrown back upon himself. It is he himself who must give content to his action.

...

It is true that this impulse is determined ideally in the unitary world of ideas; but in practice it is only by man that it can be taken from that world and translated into reality. The grounds for the actual translation of an idea into reality by man, monism can find only in man himself. If an idea is to become action, man must first want it, before it can happen. Such an act of will therefore has its grounds only in man himself. Man is then the ultimate determinant of his action. He is free.